Key Takeaways

- •India is piloting blockchain-based land registries and property tokenization across various levels, including statewide pilots and district-level deployments.

- •Platforms are emerging to enable fractional real estate ownership through tokenization.

- •Significant legal and technical hurdles remain, such as outdated property laws, data scaling issues, and building trust in the digital infrastructure.

- •Successful implementation could lead to reduced property disputes, increased transparency, enhanced liquidity, and more accessible property investment.

The Vision for Blockchain in Land Management

India is actively exploring the use of blockchain technology for its land registry system. This innovative approach proposes storing property ownership records on a distributed ledger, aiming to create a secure, tamper-proof, and transparent system. This initiative builds upon the existing Digital India Land Record Modernization Programme (DILRMP), which has been working to digitize land records nationwide.

Recent developments include a sandbox pilot in Maharashtra for property tokenization using blockchain. This means that portions of real estate assets could be transformed into tradeable digital tokens residing on the blockchain. A platform named Landbitt has also been launched in India, specifically designed to tokenize real estate and facilitate fractional ownership, allowing investors to acquire digital tokens representing shares of land parcels.

At a local level, the Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh has successfully digitized over 700,000 land records and anchored them on the Avalanche blockchain, in collaboration with a blockchain startup. Furthermore, the Supreme Court of India has officially recommended that the federal government adopt blockchain-based property registration to enhance security and combat fraud.

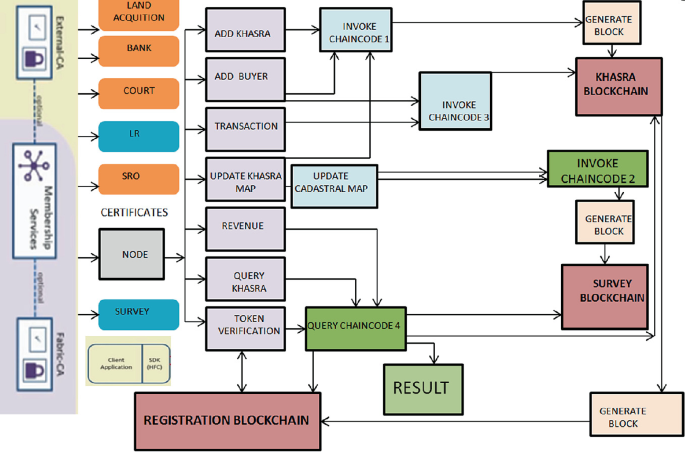

To construct this advanced system, Indian planners are focusing on integrating blockchain technology with existing land registry frameworks. A strategy paper from NITI Aayog outlines how a distributed ledger for land records could consolidate legacy paper deeds, maps, and cadastral data into a unified, modern system. Concurrently, India is developing a Unique Land Parcel Identification Number (ULPIN) for each land parcel, envisioned as an "Aadhaar for land."

Legal and Technical Challenges

The implementation of a blockchain-based land registry in India faces considerable challenges. Legally, numerous existing property laws require substantial updates. The Supreme Court has suggested reforms to acts like the Transfer of Property Act and the Registration Act to ensure that blockchain-based titles are recognized as "conclusive" rather than merely recorded entries. Without these legislative changes, blockchain records or tokens may not hold the same legal standing as traditional property deeds.

Technically, scalability is a primary concern. Applying blockchain to real-world property transactions involves managing vast amounts of data, including detailed maps, survey records, and deed copies. A critical trade-off exists between placing all records directly on-chain, which can be costly and raise privacy issues, and storing only verification hashes on-chain, which maintains proof but keeps sensitive data off-chain.

Building trust in the blockchain infrastructure is another significant hurdle, as many landowners and officials may be hesitant to adopt the new technology. There is also a risk of misuse of tokenized property if regulatory frameworks are not sufficiently robust. Fractional ownership, where a land parcel is divided into tokens, introduces complex questions regarding legal title ownership, governance, and decision-making processes among multiple token-based co-owners.

Furthermore, the underlying public infrastructure must be prepared for this technological shift. For a blockchain land registry to function effectively, state and local governments need a strong digital infrastructure, including reliable internet connectivity, secure network nodes, and adequately trained personnel. Without these foundational elements, the aspiration for a transparent, decentralized registry may not be fully realized.

Broader Implications for Real-World Asset Adoption

Should India successfully establish a blockchain-based land registry, the potential impact could be profoundly transformative. By tokenizing property, real-world assets like land can achieve greater liquidity. This means individuals could buy and sell digital tokens representing land, rather than needing to acquire an entire plot. This democratization of property investment makes it more accessible to a wider range of individuals with varying capital levels.

For the broader economy, this initiative could unlock value currently tied up in illiquid assets, enabling landowners to monetize underutilized parcels. Investors might begin to view tokenized real estate as a distinct digital asset class, injecting new capital into real estate markets. The increasing tokenization of property could also spur innovation in public infrastructure, as ownership and usage rights become more transparently governed.

On a social level, a blockchain land registry could significantly reduce land disputes. The immutable nature of blockchain records would minimize the possibility of fraudulent or duplicate deeds, thereby enhancing legal clarity around land ownership and inheritance. Over time, such a system has the potential to decrease property-related litigation, offering relief to ordinary citizens who often endure lengthy and arduous legal battles over land.

At a more visionary level, tokenized land could become an integral part of a Web3 economy for real-world assets, demonstrating blockchain's utility beyond cryptocurrencies and into essential infrastructure. A successful Indian model could serve as an inspiration for other nations, potentially establishing a global benchmark for how blockchain finance can integrate property, public infrastructure, and modern technology in a fair and transparent manner.

Conclusion

India's pursuit of a blockchain land registry represents more than a technological experiment; it is a determined effort to fundamentally reshape how property is owned, traded, and verified. By merging real-world assets like land with blockchain technology, India is making a strategic bet that property tokenization will lead to more liquid, transparent, and accessible ownership.

However, success is not guaranteed. Critical legal reforms are necessary to align with technological advancements. Technical systems must be robust and reliable, and public infrastructure needs to be capable of supporting a distributed ledger. Crucially, trust must be cultivated, particularly among individuals accustomed to traditional property documentation and in-person registration processes.

If India can navigate these challenges effectively, the long-term benefits could be substantial. Land disputes may diminish, and the property market could open up to a broader segment of the population. Public infrastructure projects might be planned and executed with greater efficiency, and real estate investment could become more inclusive. Most significantly, India's pioneering move could illustrate to the world that blockchain is not merely a tool for digital currencies but a powerful instrument for tangible, real-world change, one land parcel at a time.