The CLARITY Act and Stablecoin Debate

The CLARITY Act battle centers on yield-bearing stablecoins, not deposit outflows but shifting deposit structures that threaten banks’ zero-cost funding and payment fee dominance. Amid ongoing market debates, the core point of contention surrounding the CLARITY Act has increasingly converged on so-called “yield-bearing stablecoins.” Specifically, in order to secure support from the banking sector, the GENIUS Act passed last year explicitly prohibited yield-bearing stablecoins. However, the law only stipulates that stablecoin issuers themselves are not allowed to pay holders “any form of interest or yield.” It does not restrict third parties from offering returns or rewards on top of stablecoins. This perceived “workaround” has drawn strong opposition from the banking industry, which is now seeking to revisit the issue through the CLARITY Act by banning all forms of yield-generation mechanisms related to stablecoins. Such efforts, however, have met fierce resistance from segments of the crypto industry, most notably Coinbase.

Bank Deposit Outflows: A Misleading Narrative

In opposing yield-bearing stablecoins, the most frequently cited argument from banking industry representatives is the fear that stablecoins could trigger large-scale deposit outflows from banks. Last Wednesday, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan stated during an earnings call that “as much as $6 trillion in deposits (roughly 30% to 35% of all U.S. commercial bank deposits) could migrate into stablecoins, thereby constraining banks’ ability to lend to the broader U.S. economy… and yield-bearing stablecoins could further accelerate this outflow.”

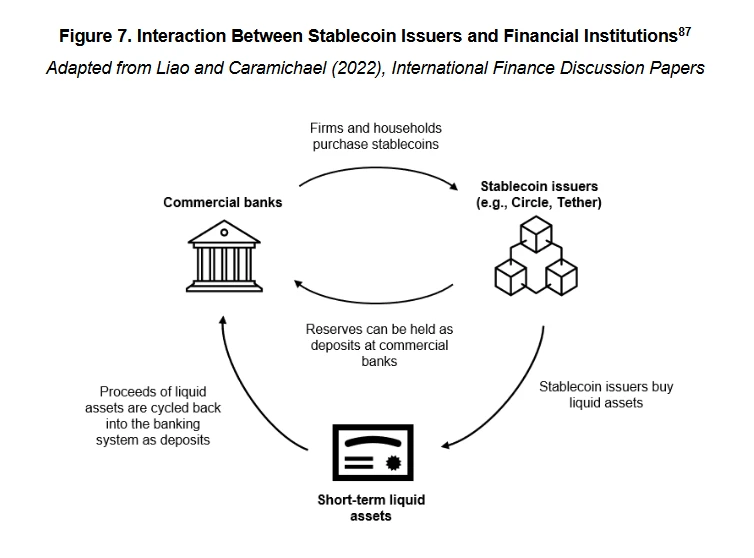

However, anyone with a basic understanding of how stablecoins actually function can immediately see that this argument is highly misleading. When $1 flows into a stablecoin system such as USDC, that dollar does not disappear from the financial system. Instead, it is placed into the reserve treasury of the issuer—such as Circle—and ultimately flows back into the banking system in the form of cash deposits or other short-term liquid assets, such as U.S. Treasury bills.

The reality is therefore quite clear: stablecoins do not cause a net outflow of bank deposits. Funds ultimately return to the banking system and remain available for credit intermediation. This outcome depends on the business model of the stablecoin, not on whether it is yield-bearing. The real issue lies elsewhere—specifically, in how the structure of deposits changes after those funds flow back into the system.

The Cash Cow of America’s Mega Banks

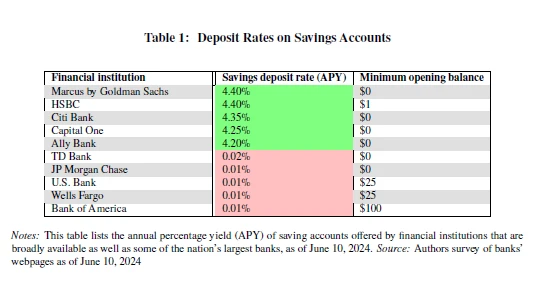

Before examining this structural shift in more detail, it is worth briefly outlining how major U.S. banks generate yield from deposits. Van Buren Capital general partner Scott Johnsson, citing a paper from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), notes that since the 2008 financial crisis severely damaged trust in the banking system, U.S. commercial banks have gradually diverged into two fundamentally different models when it comes to deposit gathering: high-rate banks and low-rate banks.

These terms are not formal regulatory classifications, but rather widely used market descriptors. In practice, the interest rate spread between high-rate and low-rate banks has exceeded 350 basis points (3.5%).

Why does the same dollar of deposits earn such drastically different returns? The reason lies in business models. High-rate banks are typically digital banks or institutions whose operations are more heavily oriented toward wealth management and capital markets (such as Capital One). They rely on higher deposit rates to attract funds in order to support lending or investment activities. By contrast, low-rate banks are dominated by national systemically important institutions such as Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo. These banks command the real pricing power in the industry. With massive retail customer bases and entrenched payment networks, they can rely on customer stickiness, brand strength, and branch convenience to maintain extremely low deposit costs—without competing on interest rates.

From a deposit composition perspective, high-rate banks tend to rely primarily on non-transactional deposits, meaning funds held mainly for savings or yield. These deposits are more interest-rate sensitive and therefore more expensive for banks to fund. Low-rate banks, on the other hand, are dominated by transactional deposits, used primarily for payments, transfers, and settlement. Such deposits are highly sticky, turn over frequently, and earn minimal interest—making them the most valuable form of bank liabilities.

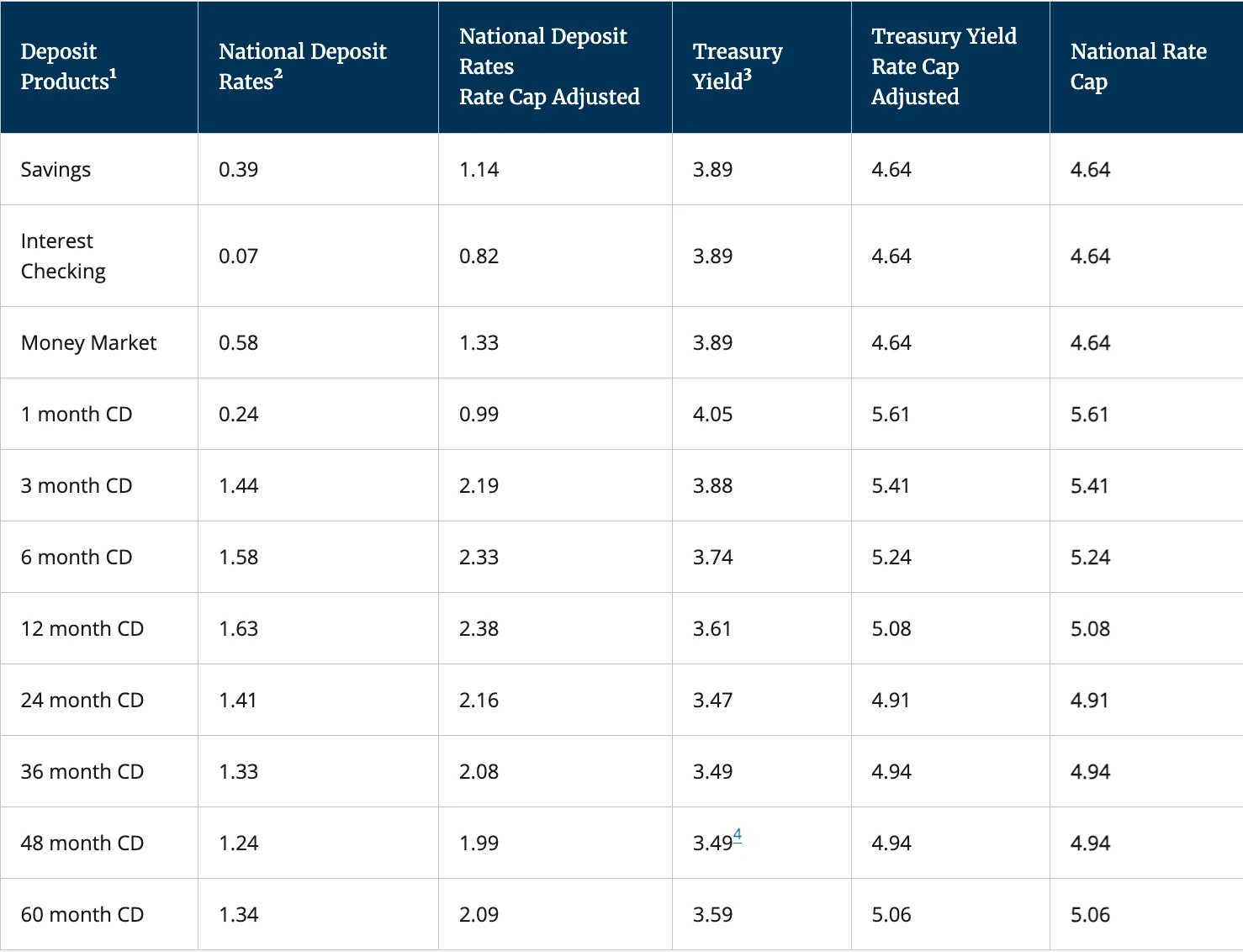

According to the latest data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), as of mid-December 2025, the average annual interest rate on U.S. savings accounts stood at just 0.39%. Importantly, this figure already includes the influence of high-rate banks. Since the dominant U.S. banks overwhelmingly operate under a low-rate model, the actual interest they pay to depositors is far below this average. Mike Novogratz, founder and CEO of Galaxy, stated bluntly in a CNBC interview that large banks pay depositors almost nothing—roughly 1 to 11 basis points—while the Federal Reserve’s benchmark rate during the same period stood between 3.50% and 3.75%. This spread alone generates enormous profits for banks. Coinbase Chief Policy Officer Faryar Shirzad offered an even clearer breakdown: U.S. banks earn approximately $176 billion annually from the roughly $3 trillion they hold on deposit at the Federal Reserve, and an additional $187 billion per year from transaction fees charged to depositors. From deposit spreads and payment-related activity alone, banks generate over $360 billion in annual revenue.

The Real Shift: Deposit Structure and the Redistribution of Profits

Returning to the core question, how does the stablecoin system reshape bank deposit structures—and how do yield-bearing stablecoins accelerate this shift? The logic is actually straightforward. What are stablecoins primarily used for? Payments, transfers, settlements, and related functions. Sound familiar?

As discussed earlier, these functions are precisely the core utility of transactional deposits. They also represent the dominant deposit category for large banks—and the most valuable form of bank liabilities. This is where the banking industry’s true concern lies: stablecoins, as a new transactional medium, directly compete with transactional deposits on a functional level.

If stablecoins did not offer yield, the threat would be limited. Given the friction of onboarding and the marginal interest advantage of bank deposits—however small—stablecoins would be unlikely to pose a serious challenge to large banks’ core deposit base.

However, once stablecoins are allowed to generate yield, interest rate differentials begin to matter. Under these conditions, an increasing share of funds may migrate from transactional deposits into stablecoins. While these funds ultimately still flow back into the banking system, stablecoin issuers—driven by profitability—would allocate the majority of their reserves into non-transactional deposits, retaining only a limited amount of cash to meet daily redemption needs.

This is the essence of the deposit structure shift. The money remains within the banking system, but banks face materially higher funding costs as interest margins compress, while revenues from transaction fees decline sharply.

At this point, the nature of the problem becomes clear. The banking industry’s fierce opposition to yield-bearing stablecoins has never been about whether total deposits leave the banking system. It is about changes in deposit composition—and the resulting redistribution of profits.

Before stablecoins—and especially before yield-bearing stablecoins—U.S. large commercial banks firmly controlled transactional deposits, a funding source with near-zero or even negative cost. They captured risk-free income from the spread between deposit rates and benchmark rates, while continuously collecting fees from payments, settlements, and clearing services. This formed an exceptionally stable closed-loop system, one that required almost no sharing of returns with depositors.

The emergence of stablecoins fundamentally disrupts this loop. On one hand, stablecoins closely mirror transactional deposits in function, covering payments, transfers, and settlement use cases. On the other hand, yield-bearing stablecoins introduce returns into the equation, allowing transactional funds—previously insensitive to interest rates—to be repriced.

Throughout this process, funds do not exit the banking system. What changes is banks’ control over the profits derived from those funds. Liabilities that were once nearly cost-free are forced to become market-priced. Payment fees once monopolized by banks are now partially diverted to stablecoin issuers, wallets, and protocol layers.

This is the transformation banks simply cannot accept. And once this is understood, it becomes easy to see why yield-bearing stablecoins have emerged as the most contentious—and least negotiable—battleground in the CLARITY Act’s legislative journey.